October 2024

Surgicel – A mimic of Pseudo-recurrence of Lung Adenocarcinoma

Dr Sesha Kanagasabai, Foundation Year Doctor (FY2) - Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

Dr Peter Tcherveniakov, Consultant Thoracic Surgeon - Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Dr Annette Johnstone, Consultant Cardiothoracic Radiologist - Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

Case history

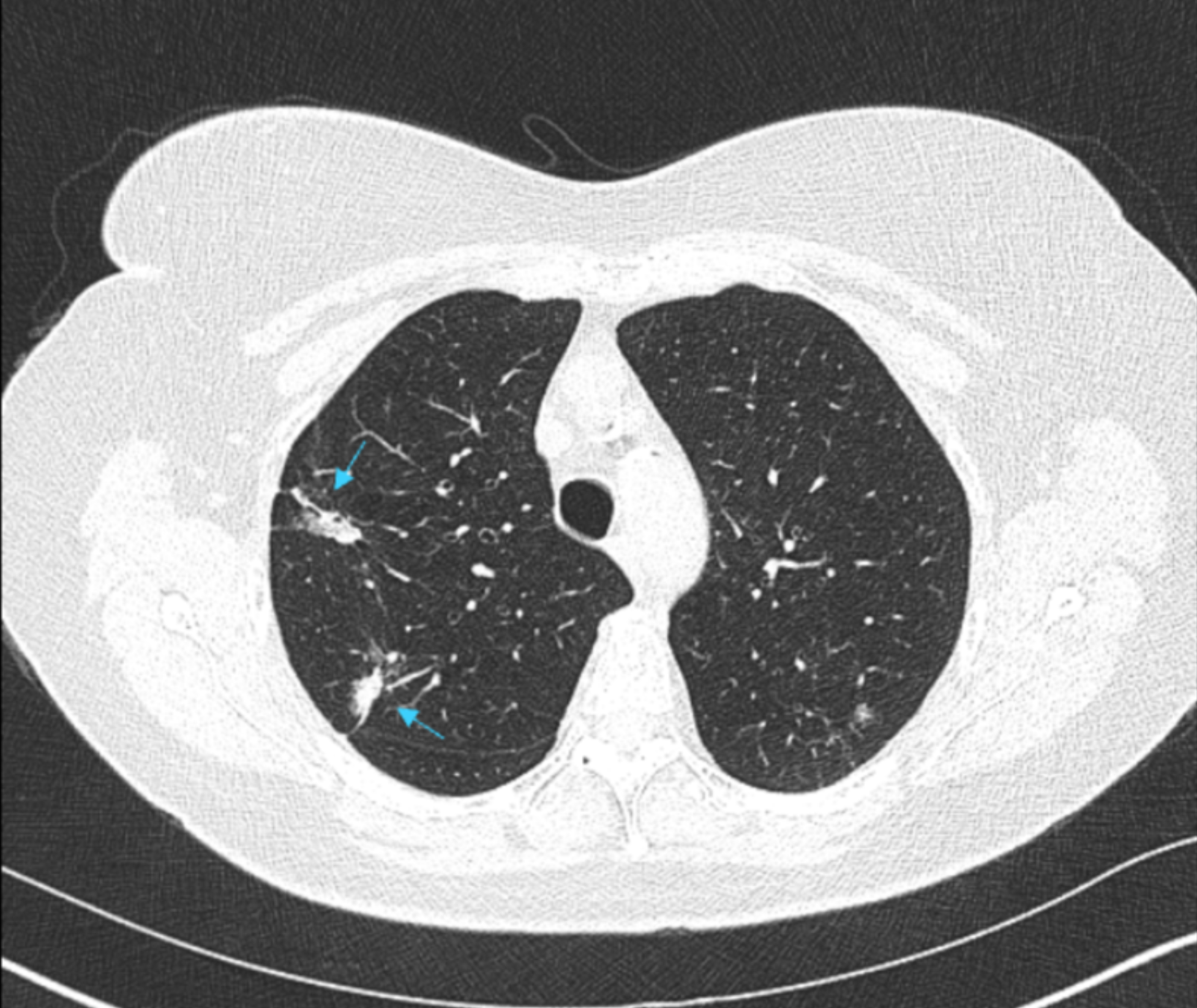

A 62-year-old female was diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast and was under investigation for possible bowel cancer. Radiotherapy-planning for breast cancer demonstrated two part-solid lung nodules (PSNs) in the right upper lobe (Fig 1). Consequent nodule surveillance demonstrated growth and an increase in size of the solid component over a 24 month period. The patient subsequently underwent a CT-guided lung biopsy of the larger solid nodule and results confirmed evidence of lung adenocarcinoma.

Fig 1. Radiotherapy-planning CT demonstrated two part-solid lung nodules (PSNs) in the right upper lobe.

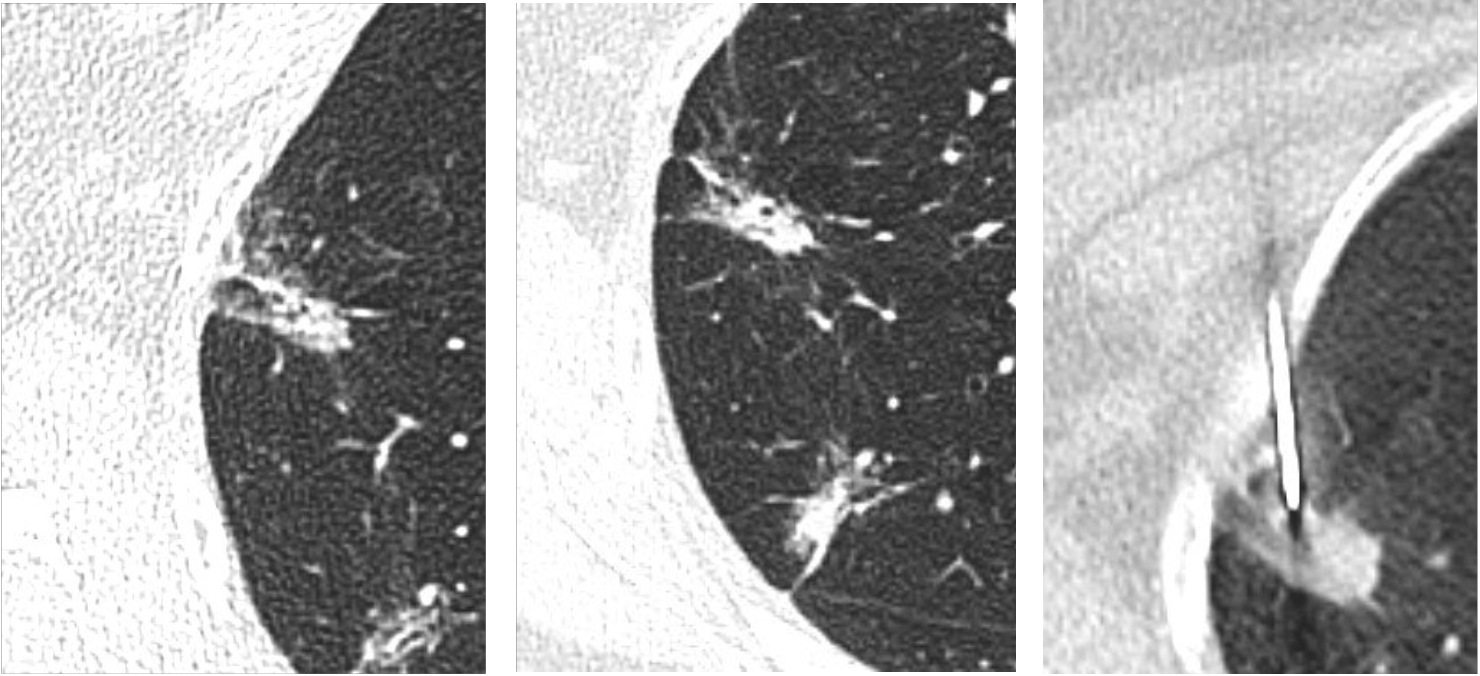

Fig 2. Progressive increase with subsequent biopsy

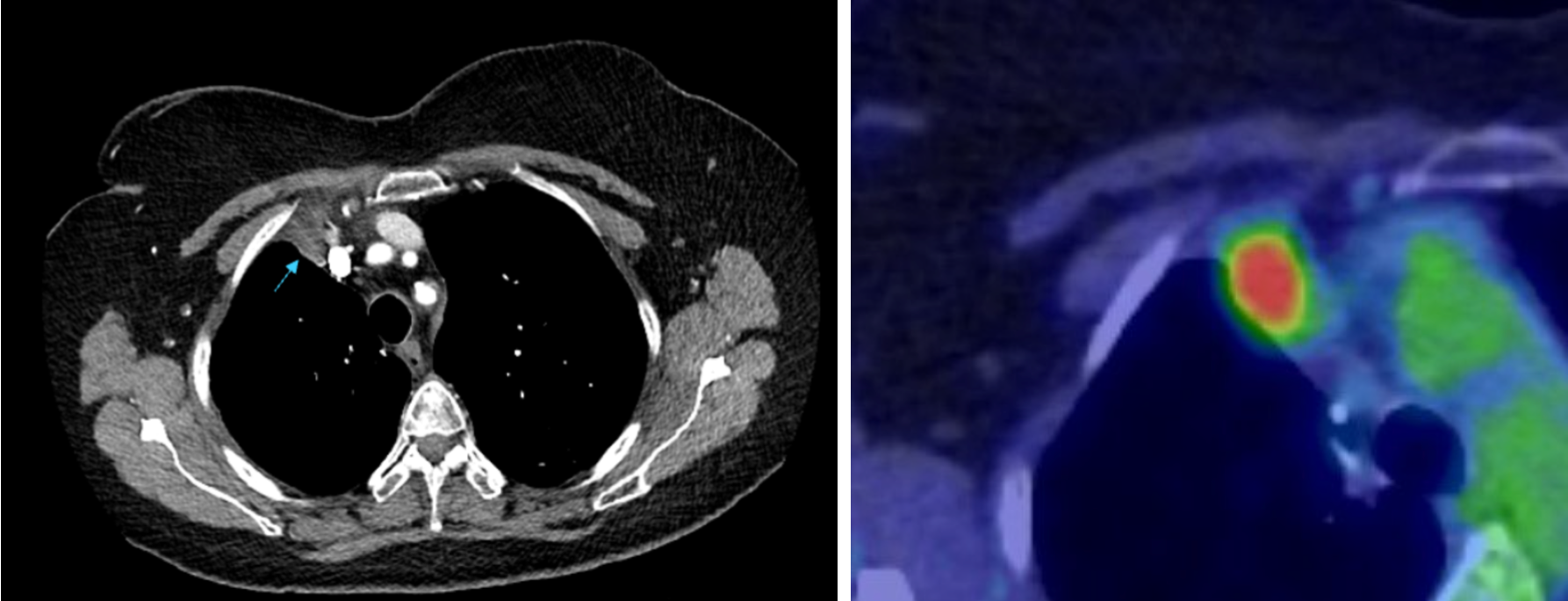

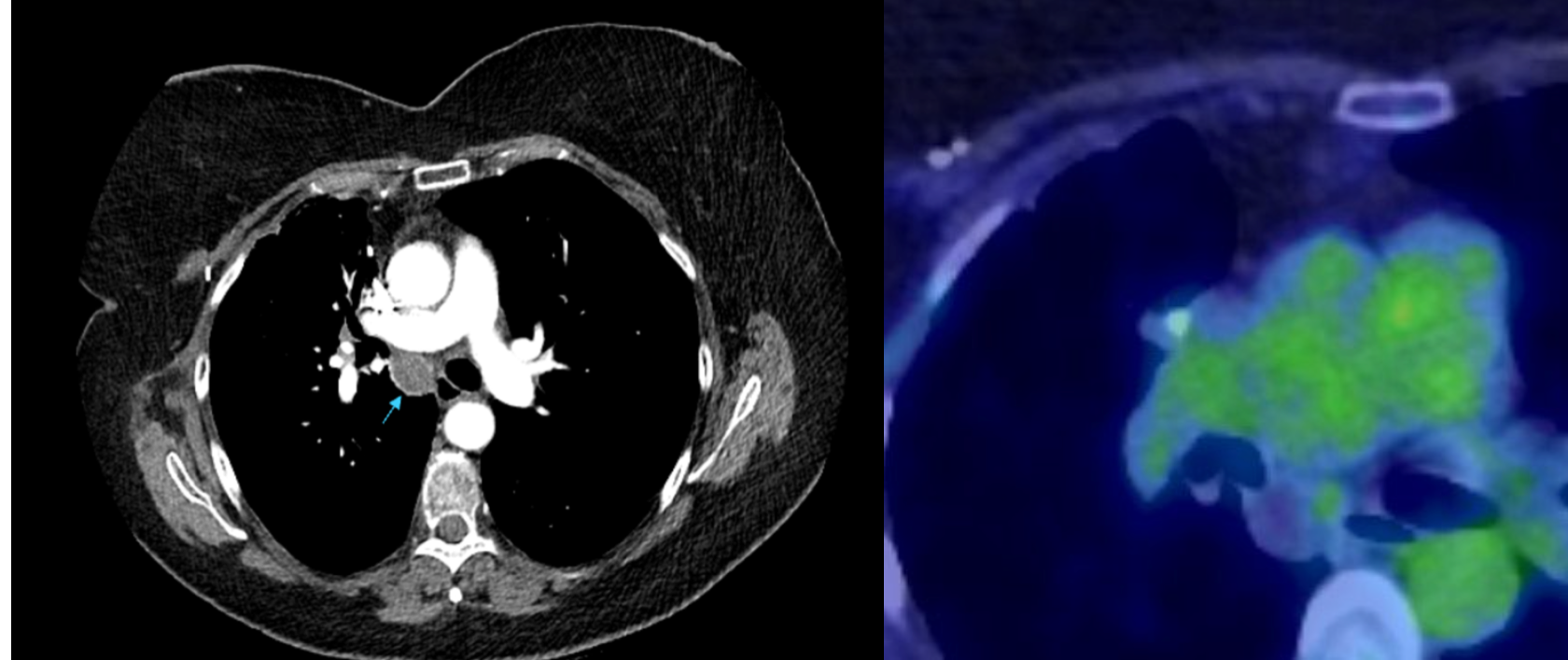

Shortly afterwards the patient underwent a right upper lobectomy and had survivorship CT performed 3 months post operatively. Follow-up imaging demonstrated two new abnormalities suspicious for recurrence of disease. An anteriorly positioned peripheral lesion measuring 22 mm, suspicious for surgical margin recurrence (Fig 3) and a separate central lesion measuring 21 mm, concerning for Station 7 subcarinal nodal disease (Fig 4). FDG PET-CT was therefore performed which displayed avidity of the peripheral lesion.

Fig 3. Anterior lesion with corresponding FDG PET-CT image

Fig 4. Central lesion with corresponding FDG PET-CT image

The previous lobectomy specimens were reviewed which confirmed full resection of the initial nodules with pR0 margins. Further CT-guided biopsy and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) were utilised to investigate these new areas of concern. Interestingly, pathology results were in keeping with a reactive station 7 lymph node for the central lesion and a reaction to the surgical haemostatic gauze (Surgicel) for the peripheral lesion. Continued surveillance demonstrated slow regression of the station 7 node.

Discussion

Surgicel ™ (oxidised regenerated cellulose) is a sterile fabric meshwork commonly used as a local haemostatic adjunct in surgical procedures to aid capillary, venous, or small arterial haemorrhage-control. (1) Owing to its bioabsorbable and bactericidal properties, it is left in the surgical bed following the procedure to induce haemostasis. Surgicel provides a matrix for platelet aggregation and adhesion which upon saturation with blood, swells into a gelatinous mass. (1,2) According to product literature from Ethicon, it is usually absorbed in seven to fourteen days. (1) However, the rate of reabsorption has been seen to be affected by the quantity of Surgicel used, its site of use, and environmental factors which may delay this process to up to eight weeks. (3)

Due to its acidic nature, Surgicel has been found to trigger acute and chronic localised inflammatory changes, granulation tissue development and fibrous capsule formation which may resemble tumours on CT. (4) Furthermore, during its degradation, it is hypothesised that air is trapped within the spaces of the haemostatic gauze material. (5,6) This phenomenon is thought to be the cause for the appearance of trapped air bubbles occasionally seen on radiological imaging, thus mimicking abscess cavities or collections. Features which may allow differentiation of Surgicel from an abscess on imaging include the absence of rim enhancement or an air-fluid level. (5)

Additionally, Surgicel, when left in the surgical bed in abdominal, (3) lung, (7) and cardiac surgery (8) has been seen to cause hyper-uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) on FDG PET CT. Hyper uptake has been observed to persist for up to 12 months post lung surgery, two to six months post abdominal surgery, and nearly two years post cardiac surgery. (3,7,8) These false-positive findings on PET CT may be misconstrued for abscess cavities, malignant recurrence, enlarged lymph nodes or intracardiac infections.

Therefore, it is imperative that the patient’s intraoperative details are carefully documented and specify the use of haemostatic gauze such as Surgicel and its exact location. It is also crucial that radiological images are interpreted with consideration of these intraoperative details to avoid diagnostic errors.

References

- SurgicelTM original absorbable hemostat | ethicon | J&J medtech (2022) Johnsosn & Johnson MedTech. Available at: https://www.jnjmedtech.com/en-US/product/surgicel-original-absorbable-hemostat (Accessed: 23 June 2024).

- Roshkovan, L. et al. (2021) ‘Multimodality imaging of surgicel®, an important mimic of post-operative complication in the thorax’, BJR|Open, 3(1). doi:10.1259/bjro.20210031.

- WANG, H. and CHEN, P. (2013) ‘Surgicel® (oxidized regenerated cellulose) granuloma mimicking local recurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report’, Oncology Letters, 5(5), pp. 1497–1500. doi:10.3892/ol.2013.1218.

- Tomizawa, Y. (2005) ‘Clinical benefits and risk analysis of topical hemostats: A Review’, Journal of Artificial Organs, 8(3), pp. 137–142. doi:10.1007/s10047-005-0296-x.

- Tam, T. et al. (2014) ‘Oxidized regenerated cellulose resembling vaginal cuff abscess’, JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons, 18(2), pp. 353–356. doi:10.4293/108680813x13693422518597.

- Frati, A. et al. (2013) ‘Accuracy of diagnosis on CT scan of Surgicel® Fibrillar: Results of a prospective blind reading study’, European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 169(2), pp. 397–401. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.04.008.

- López Sánchez, J. and Gómez Hernández, M.T. (2021) ‘Strange body reaction by Surgicel® simulating lymph node relapse on PET/CT after lung cancer surgery: 3 new cases’, Revista Española de Medicina Nuclear e Imagen Molecular (English Edition), 40(3), pp. 202–203. doi:10.1016/j.remnie.2020.10.001.

- Martínez, Amparo et al. (2021) ‘Surgicel-related uptake on positron emission tomography scan mimicking prosthetic valve endocarditis’, The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 112(5). doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.02.046.